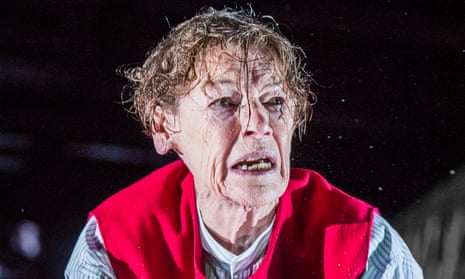

It would be easy to regret Glenda Jackson’s 25-year absence from the stage but she has lost none of her innovative instinct. I suspect her experience of political life and the world’s injustice has enriched her understanding of Lear. Even if I jib at the conventional pieties surrounding Shakespeare’s flawed tragedy, there is no doubting that she is tremendous in the role. In an uncanny way, she transcends gender. What you see, in Deborah Warner’s striking modern-dress production, is an unflinching, non-linear portrait of the volatility of old age. Jackson, like all the best Lears, shifts in a moment between madness and sanity, anger and tenderness, vocal force and physical frailty.

Her great gift, however, is to think each moment of the play afresh. She enters, without undue ceremony, hand in hand with her beloved Cordelia. But there is irony when she announces, in a self-mocking drawl, that she will “crawl” unburdened towards death. Having routinely given Goneril and Regan their share of the kingdom, she ecstatically cries “Now our joy” on turning to Cordelia, and initially greets her refusal to play the game with incredulous laughter. But instantly this turns to violence as she hurls Cordelia to the floor and rushes at Kent with one of the blue chairs that adorn the set. Yet, even here, the mood swiftly changes as Jackson registers the banished Kent’s departure with a derisive regal wave.

If I describe the opening scene in detail, it is because it lays the ground for everything that follows. It shows Lear’s fatal partiality, capricious waywardness, even wild humour. All these qualities come into play in Jackson’s brilliantly jagged reading of the part. Scorned by her elder daughters, she parodies her supposed decrepitude while quietly winking at the Fool. Yet there is ferocity in the vulpine claws she extends towards Goneril. And when Regan asks why she needs even one follower, Jackson makes “O reason not the need” less an earth-rending cry than a simple utterance of despair, delivered head in hands, at human incomprehension.

Even Jackson cannot reconcile me to the gobbledegook of the hovel scene but she is superb in the play’s later stages. The pathos of the confrontation with the blinded Gloucester is overshadowed by Lear’s rage at the world’s inequity: Jackson gives especial force to “The strong lance of justice hurtless breaks”, reminding me of Michael Pennington’s observation that Lear becomes a socialist. Right to the end, Jackson embodies Lear’s contradictions: while tenderly clutching the dead Cordelia, she spits with vengeful fury at “you murderers, traitors all”.

Warner’s production offers a clear framework for a shattering performance. She and Jean Kalman have created a simple design composed of rectangular white flats: at one point, one spins round to reveal the beer-stocked fridge at Goneril’s house. The storm is evoked through billowing black sheets, looking like large bin liners, and a projected rainstorm. A perspective of distant blue sea tells us we are in Dover. Some of the details are decidedly peculiar: both Edmund and Edgar display their buttocks to the audience making me wonder if mooning is a family trait. And when Regan hurled part of Gloucester’s gouged eye into the audience, I worried that, as the panto season approaches, someone might throw it back.

The surrounding performances are also variable. Rhys Ifans over-colours every line of the Fool, even venturing into a cod Bob Dylan tone when he sings a snatch of folk: I began to think nostalgically of the way Paul Scofield’s Lear and Alec McCowen’s Fool simply sat side by side on a bench in Peter Brook’s celebrated production. But Celia Imrie’s grimly determined Goneril and Jane Horrocks’s sexually excitable Regan are sharply distinguished. Morfydd Clark as Cordelia intriguingly suggests a belated passion for Sargon Yelda’s Kent. And although Edgar’s argument that he fails to reveal himself to Gloucester to save his father from despair strikes me as nonsensical, Harry Melling lends the role a believable integrity.

Even if Hamlet and Macbeth are greater plays, Jackson’s performance catches perfectly the zigzag patterns of Lear’s mix of insight and insanity. This is “reason in madness” to the very life.

At the Old Vic, London, until 3 December. Box office: 0844-871 7628.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion