President Donald Trump's envoy to Afghanistan is intensifying efforts to pull the Taliban into a peace deal that will end America's longest war, holding a flurry of meetings in the region over the past four months.

The Taliban said talks were being held Monday with Zalmay Khalilzad, the U.S. diplomat tasked with negotiating with the group that once sheltered Osama bin Laden.

While American officials would not confirm that Khalilzad was in the United Arab Emirates, the State Department says he has met and will continue to meet "with all interested parties" in the conflict.

Khalilzad has stressed he is "in a hurry" to secure an agreement, a sign of how eager the White House is to withdraw the 15,000 U.S. troops remaining in Afghanistan.

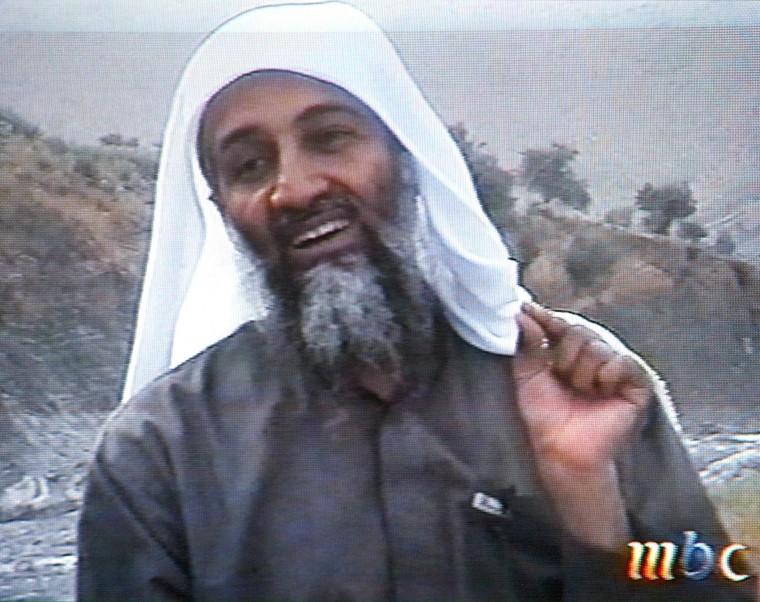

But even as diplomatic efforts gallop ahead, a crucial question looms over talks: Would a Taliban legitimized by an international peace agreement prevent foreign terrorists from plotting attacks from Afghan soil like Al Qaeda did before Sept. 11, 2001? It was the Taliban government's decision to protect bin Laden that triggered the subsequent U.S.-led invasion.

Top military brass clearly feel there is a danger of history repeating.

“Were we not to put the pressure on Al Qaeda, ISIS and other groups in the region that we are putting on today, it is our assessment that in a period of time their capability would reconstitute,” Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Joseph Dunford said earlier this month at an event organized by the Washington Post. “They have today the intent and would have in the future the capability to do what we saw on 9/11.”

Bin Laden funneled money, weapons and fighters into Afghanistan during the Soviet occupation, which began in 1979. He founded Al Qaeda about a decade later. After being banished from Saudi Arabia, bin Laden established a base in Afghanistan in 1996, launching a series of attacks on Western targets that culminated in the 9/11 attacks.

So far a 17-year military campaign along with billions in aid have not succeeded in driving out the Taliban and other militants. In 2017, Afghanistan overtook Iraq to become the deadliest country for terrorism, with one-quarter of all such deaths worldwide happening there.

More than 2,400 American lives have also been lost in Afghanistan since 2001. And according to the Pentagon, the war is costing U.S. taxpayers around $45 billion per year.

“Even after 9/11, the Taliban was not willing to give up Al Qaeda.”

Despite years of fighting, only around 65 percent of the Afghan population lives in areas under government control.

Reflecting the sense they have the upper hand on the battlefield, or at very least reached a stalemate, the Taliban is keen to show it is no longer beholden to international terror groups. It is also trying to portray itself as ready to re-enter the official halls of power.

So the militant group is counting on war weariness outweighing U.S. fears of the 20 or so “transregional” terrorist groups thought to be operating in and around Afghanistan.

A senior Afghan Taliban commander who is also a member of the group’s leadership council told NBC News that there were around 2,000 to 3,000 non-Afghan fighters in their midst, mostly from China, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Chechnya, Tunisia, Yemen, Saudi Arabia and Iraq.

"We are Muslims and according to our religion ... we cannot deny shelter to someone if he or she comes to trouble," said the commander, who recently attended three days of talks with Khalilzad in Qatar. “None of the foreign militants would be allowed to take up arms and use this soil against any country in the world.”

Thousands of Pakistanis are also thought to be fighting as members of the Taliban.

Bin Laden also attracted foreign fighters to Afghanistan after relocating there when the country was ruled by the Taliban, so the question of how the group would deal with the issue still resonates in Washington.

Ahmed Rashid, who is considered one of the world’s leading authorities on the Taliban and Afghanistan, estimated that between 2,000 and 3,000 Arabs under bin Laden fought with the Taliban before 9/11, as did tens of thousands of Pakistani militants and a smaller number of Uzbek radicals. The number of foreign fighters in Afghanistan the 1980s stood at around 35,000, according to Rashid.

Despite 17 years of U.S. counter-terrorism fighting in Afghanistan, a greatly weakened Al Qaeda still operates in pockets of the country. In August, Afghan defense officials said its militants had been part of a Taliban's assault in the east of the country. And in November, an American soldier was killed in battle with Al Qaeda militants in the southwest.

“Even after 9/11, the Taliban was not willing to give up Al Qaeda,” said Vanda Felbab-Brown, an expert on international terrorism and a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, a Washington-based think tank. “Although since the mid-2000s, the Taliban was periodically telling the U.S. that they would not support Al Qaeda, they have never been willing to say it publicly on the record.”

It would be politically costly to “just disavow their brethren,” she said.

This is partly because after the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in 1979, the country became a magnet for cash and a training ground for thousands of jihadis. Bin Laden raised funds to help expel “infidel” Russian troops in a cause that galvanized a generation of mujahedeen, or holy warriors, and still reverberates throughout the Muslim world.

“I don’t think that the Taliban loves Al Qaeda,” Felbab-Brown said. “But it does not necessarily mean that they can easily control them.”

Even if they wanted to, it is unlikely that the Taliban could keep a promise to rein in foreign fighters and groups. For one thing, the central government in Kabul has always struggled to control the country.

And then there is ISIS Khorasan, the Islamic State’s local affiliate which includes many disaffected Taliban fighters. While small in number, the group has been especially brazen and lethal.

Other groups with regional ambitions, such as Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed — both of which fight for Indian-controlled Kashmir to separate and become part of Pakistan — have operated “independently, or even in contradiction to the Taliban,” Felbab-Brown added.

The Taliban counters that in the 17 years that it has been fighting U.S. and Afghan forces, not a single attack outside the country has emanated from Afghanistan.

Today's Taliban is much more self-reliant, according to Seth Jones, a former special operations officer in Afghanistan and the director of the transnational threats program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington think tank.

When giving shelter to bin Laden before 9/11, the Taliban could count on an influx of financial help and fighters from abroad — particularly from conservative Sunni Gulf kingdoms.

But the group has diversified its income and is involved in everything from poppies — the source of opium — to the timber business, Jones said.

“Taliban commanders at the local level are quite innovative in finding sources of income [and] taxation on areas,” he said. “I have no worries that the Taliban can find sources of money.”

Of special concern is continued support for the Taliban from neighbor Pakistan, which has long provided support for the group. Frustration with this prompted Trump to cancel $300 million in aid to Pakistan in September.

Pakistani officials reject claims they help or shelter Afghan militants.

Experts also say it appears doubtful the Taliban would ever be able to fully control the country. This leaves open the possibility that groups such as ISIS, which the Taliban has been battling, will set up strongholds and terrorists intent on attacking targets beyond Afghanistan's borders.

“The challenge is that the lure and the magnetism of the Iraq and Syria wars has subsided,” Jones said, referring to the recapture of most of the land in the Middle East once controlled by ISIS.

And as the origin of “global jihad,” Afghanistan remains “a winning cause,” he added.