July 24, 2020 | Research

Researchers show that media is trying to change old power structures, but there is still much room for improvement

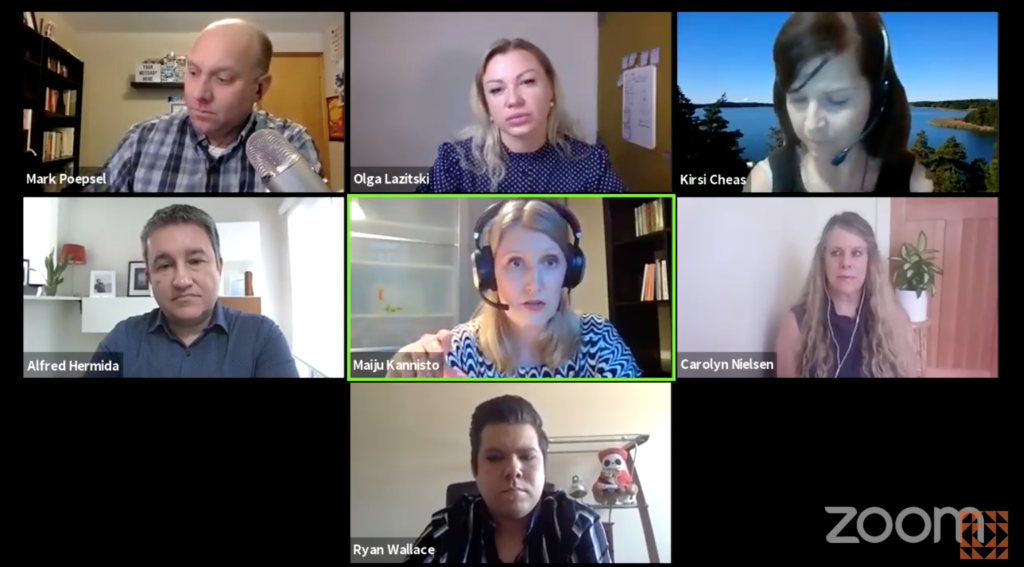

Keeping its tradition of bringing together scholars, journalists and media executives, on July 23 the 21st International Online Journalism Symposium (ISOJ) held its research panel “Power, privilege and patriarchy in journalism: Dynamics of media control, resistance and renewal” to discuss the results of peer-reviewed papers that were published in #ISOJ – the official research journal of the Symposium published every year. The research journal is celebrating its 10th anniversary this year.

The following is a summary of the work they presented.

Alfred Hermida, professor and director of the Graduate School of Journalism at University of British Columbia (Canada), and guest editor of #ISOJ Research Journal, chaired the panel.

Hermida began by explaining that the demonstrations of indigenous communities in British Columbia were one of the reasons to choose this year’s theme. According to Hermida, there was a debate regarding how media refers to these communities: some called them “protesters” while others called them “land protectors.” He explained that some of the criticism against media was that by calling them “protesters” it was the idea that “they do not have a legitimate claim to that traditional territory.”

“And it was an example of how the language the journalists use, the decisions they make in terms of how to refer and frame events like these shape the story. The language used by journalists reflects power structures, and biases built into media structures,” explained Hermida.

In that sense, the papers answer questions such as: who is journalism for, who is benefited, and who is affected. The answers to these questions could help “to acknowledge the evidence of racism, gender coverage biased in newsrooms as well as in the classrooms,” Hermida added.

Ryan Wallace, from the University of Texas, talked about “‘We Are the 200%’: How Mitú Constructs Latino American Identity Through Discourse.” According to Wallace, this year’s research theme made him think not only of the mainstream media but also of the media organizations that cater to specific demographics, such as the Latino population.

Mitú is a digital native outlet with presence in different social media platforms that seeks to speak to what they call “the 200%,” people who are 100% American and 100% Latino. Wallace sought to answer to what extent Mitú’s discourse construct a Latino American identity, and if its discourse challenges patriarchy and other ideological notions of hegemony.

One of Wallace’s findings relates to Guacardo, a sort of a mascot for the site and which he says is a “extended metaphor for Latino American significant participation in both production and consumption of popular American culture.” Wallace concluded that Mitú is “actively creating a new Latino American identify” by providing Latinos “similarities rather than differences.”

However, he considers that some decisions from Mitú could exclude some Latinos such as the use of Spanish or references that new generations might not feel related to, for instance the “telenovelas.” A situation, he thinks, could end up in echo chambers.

The situation for journalists in Russia is not easy; they must face threats, unlawful arrests and censorship, among other situations. That is why some reporters have decided to create what Olga Lazitski, from the University of California, calls “alternative professional journalism” (APJ). She said that one of the first victories of these APJs was the releasing of a journalist who was arrested for allegedly possessing drugs after a huge online and off line campaigns.

During her presentation “Alternative professional journalism in the post-Crimean Russia: Online resistance to the Kremlin propaganda and status quo,” Lazitski said that it was important to study this media because it “can help us understand the ways in which journalism can reconfigure power relations within the society in non-democratic regimens and contribute to the development of public spheres in non-Western contexts.” With her research, Lazitski wanted to know who was doing this journalism, how they did it, and whom who are the consumers.

She said she found that the tension these media outlets falls “between the neutral observer role and the civil activist role.” She said that although the majority knew that there is a type of oppression they are fighting against to (censorship, threats, etc.), they do not want to be labeled as activists. Lazitski said these new outlets try to follow the U.S. journalistic tradition: with the idea of being impartial and writing the two sides of the story.

They see themselves “outside of the system, but not a as counter propaganda,” she said. “It is a way to protect themselves, and avoid being called biased or from attacks at any time. Unfortunately, that is what is happening in Russia today.”

Mark Poepsel professor at the Southern Illinois University-Edwardsville, authored the research paper “Participatory journalism and the hegemony of men,” in which he reviewed digital participatory journalism literature that can make issues like gender visible in newsrooms.

Poepsel spoke about how participatory journalism techniques could be improved to allow a true discussion about women’s rights in newsrooms, for instance. He said that using social networks to look for women who “challenge the hegemony of men in media” and ask them for comments in different stories could be a good exercise.

Participatory journalism, according to Poepsel, creates reciprocity at a time when media needs to regain trust and the audience needs something to trust in. However, according to his research, gender issues have not been given the space to be discussed in media, and even women who speak of rights are seen as “unprofessional.”

“The field of professional journalism is fighting for its lives. If you have to choose, do you rather protect the old boys network within newsrooms or the ability to provide survival information for your audience? Do you prefer to serve democracy by informing the public or to preserve the patriarchy of power of men of certain notions of what to means to be a man or what masculinity should mean?” he said.

Kirsi Cheas and Maiju Kannisto along with Noora Juvonen from the University of Turku in Finland talked about “#MarchForOurLives: Tweeted teen voices in online news,” where they analyzed how media covered the shooting at a Parkland, Florida (United States). Their research sought to determine whether this event transformed the public discussion of gun violence through activism on Twitter.

As Kannisto explained, the Parkland shooting created a lot of activity on Twitter compared to other shootings, and because of that media also paid more attention to the information published there. Outlets such as The New York Times or CNN published a large number of tweets as part of their coverage, Kannisto added. The investigation showed that Parkland students were heard.

However, the researchers explained, the editorial line of each media influenced the way in which these voices were heard. For example, more conservative media gave voice to young pro-guns activists while more liberal ones quoted those who wanted stricter gun regulations. But ultimately “social media had significant effect on media coverage regarding Parkland shooting and the aftermath.”

Carolyn Nielsen decided to write about the media’s coverage to the harassment of congresswomen of color after President Donald Trump racistly tweeted about four women congressmen of color and then three days later he and his followers began to chant “send her back” in a rally.

This incident gave birth to the paper “Send her back: News narratives, Intersectionality, and the rise of politically powerful women of color,” in which she analyzes three media outlets in four aspects: if they called out racism; if they could see the intersectionality of women like Congresswoman Ilhan Omar (who is a naturalized American citizen, and who is the first Muslim woman in Congress); if they could see the President’s actions as part of a system; and if the media reflected the values they claimed to have.

Nielsen analyzed The Washington Post, VOX, and Buzzfeed. The first media outlet is what is considered as media legacy, VOX calls itself as “explanatory journalism,” and Buzzfeed do what is known as Journalism 3.0, focusing on what people are talking about and reporting on it.

For Nielsen, the traditional outlet did a better job dealing with these issues, but their coverage still had problems that could be fixed. “New types of journalism are talking about new values but not showing them,” Nielsen said, and added that VOX’s coverage, for instance, was not as “explanatory journalism” as it claims to be. However, she said that media outlets “have [the] potential to disrupt racism,” and that there is “good news from traditional journalism.”

Following the presentations, Amy Schmitz Weiss, ISOJ Research Chair, announced Ryan Wallace’s paper as the winner of the ISOJ Award.