A couple of weeks ago, I sat in a meeting convened by a new Institute created at Georgia State University.

Approximately 25 faculty members sat around a table to discuss the various ways in which our research engages Atlanta, with hopes of bringing the resources and expertise of Georgia State University to the larger Atlanta community. The faculty introduced themselves, their department and their research interests. A historian with interdisciplinary methodological training, I explained that I am housed in GSU’s Department of African-American Studies and that I bare the blessing and curse of studying the national and international implications of Atlanta’s notoriety as the Black Mecca. After I introduced myself, the group’s chairman asked “Maurice . . . should I watch the new FX Series Atlanta? I grinned and began: “That show is unique and funny . . . ” only to be interrupted by a white colleague, who blurted loudly, “It’s really not a comedy!” For a split second I thought, “How dare they try to police my thoughts about what comedy is and should be for me?” I immediately thought of the brutal honesty of Richard Pryor and without hesitating I responded “the FX Series Atlanta may not be funny to you because you don’t navigate that world. This is a world in which I live and interact daily and unless you know how to navigate it, you’ll miss all of the lessons hammered home in this show.”

I am in academia but not of it. As a scholar of color in a city such as Atlanta, it is important to know the difference, because outside of the walls of academia, I live and interact with good and complicated people who have not been blessed with the opportunities that I have been afforded. I enjoy living in this black city and love the research that I do, even though I am critical of Atlanta’s Black Mecca thesis. Yet, my response forced me to further consider why some audiences miss the humor of FX’s Atlanta. This essay explores those considerations, detailing Atlanta’s popular imagery as the crown jewel of the American South championing race relations; yet challenging this representation by exploring Donald Glover’s candid depiction of the city through Atlanta.

In his timeless classic, The Souls of Black Folk, the then Atlanta-based scholar W. E. B. Du Bois wrote, “The problem of the 20th Century is the problem of the color-line.” 1 He further detailed two concepts that shaped popular narratives of Atlanta. Du Bois’ articulation of double consciousness 2 and the talented tenth 3 are central to black Atlanta’s development in proximity to white America. The presence of double consciousness and the talented tenth, within the context of Henry Grady’s New South Atlanta, demonstrates a community concerned with white validation. Grady’s New South advocated industrial development as a solution to the post–civil war South’s economic and social troubles, yet excluded blacks. Atlanta’s progressive gusto hinged on a city where compromising black people harmonized with hardly tolerable whites. So it is Atlanta’s uniquely southern narrative as the “the city too busy to hate”; then the “Black Mecca”; and finally “Hotlanta” that etch indelible impressions in our public memories.

Over time, Atlanta has represented the varied outlooks of multiple communities. White Mayors William Hartsfield and Ivan Allen guided the city through the turbulent 1940s, ’50s, and ’60s by courting black support from black political kingmakers while placating whites. They attributed this alleged harmonious racial spirit to “the city too busy to hate” moniker. Black mayor Maynard Jackson’s 1973 election set in motion a quickening of the consolidation of black control of local governments and the expansion of black businesses and the black middle class, cementing in the national black consciousness Atlanta’s unique designation as the “Black Mecca,” a description first assigned to it by Ebony Magazine. 4 By the 1980s, Atlanta’s notoriety as the nation’s newest world class and international city led the Atlanta Convention and Visitors Bureau to deem her “Hotlanta,” at the behest of the city’s greatest asset, boosterism. When Atlanta was selected as the host city for the Centennial Olympiad, it was seen as a product of the visionary leadership of black Mayors Maynard Jackson Jr. and Andrew Young. The Olympic victory came thanks to a coalition of elites—cooperation between the black city government and the white business elite. The city’s boosters, the Atlanta Convention and Visitors Bureau, and different trade and tourist administrations could now claim that Atlanta had outgrown its status as regional capital of the South, transcending the region and its history. After decades of reinvention, it was the “Black Mecca” and “Hotlanta,” imagery that preceded the city rather than the Big Hustle or Sorrow City monikers. 5 Although Black Atlanta does represent the highest educational, political, and economic aspirations and achievements of blacks over the past century, there are other narratives simmering just beneath the surface unseen by white Atlantans.

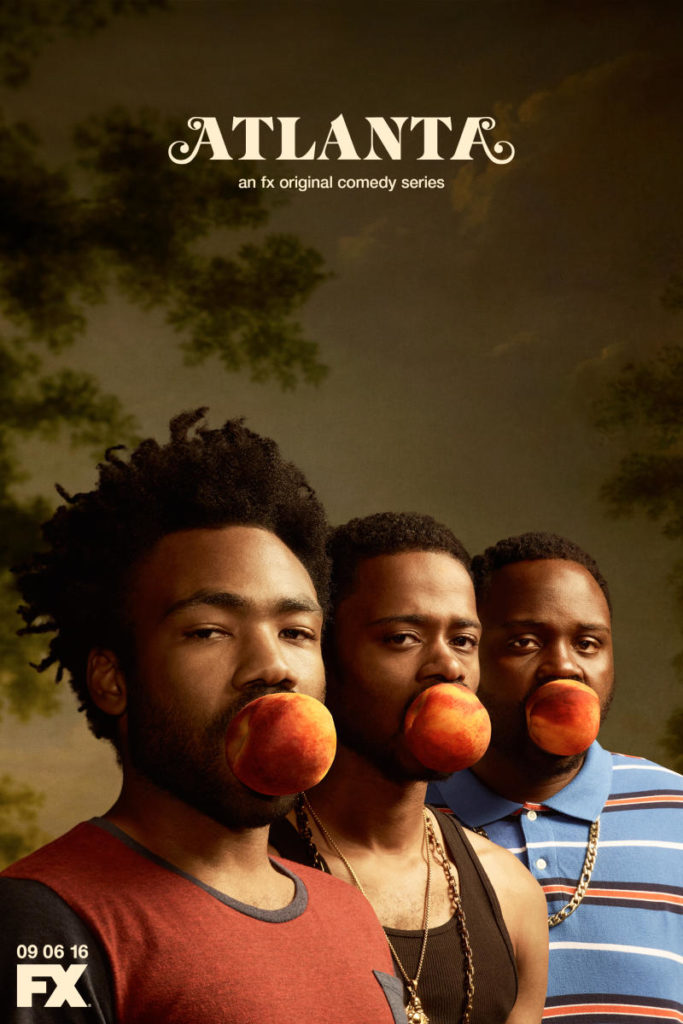

The fruits of the city’s success were not, and have never been, shared equitably. As much as Atlanta has developed, the black masses have benefitted little from the previous decades. Donald Glover’s FX Series Atlanta bears witness to this account by exploring the most discontented and deprived circumstances for black people in the South and nation. Better than perhaps any other city, Atlanta provides a platform for viewing the interactions between diverse black populations, with gut-busting humor that is central to the all-black Atlanta experience. 6

In his own words, Glover created FX’s Atlanta as “hyper-realism . . . with brief moments of surrealism . . . all which serve to disorient” viewers unfamiliar with black life in Atlanta’s blighted areas. He mused,

I had to make people feel a certain way. Let’s . . . give people a feeling that they can’t really siphon or make into something else. Most things lie in the gray area. [We] just play around in the gray areas. Stereotypes exist, but the way they exist [are] not how they are to most people. They’re usually very cartoonish. 7

He further explains that his goal was “to make Twin Peaks for rappers. The thesis of the show was kind of to show people how it felt to be black, and you can’t really write that down. You kind of have to feel it.” 8 In this, Glover asserts that Atlanta is not to be understood by audiences unfamiliar with the seedier sides of black Atlanta.

As to the rejection of Du Bois’ double consciousness and talented tenth concepts and the complicated nature of black respectability politics, Glover asserted, “I’m less interested in showing what should be, and more interested in showing what is, from my perspective.” 9 Here, Glover dismisses black respectability politics, which in this context, privileges black art – the anecdotes and aesthetics of black Atlanta life – to present propaganda promoting positive images of black living experiences. Instead, “[Glover wants people to] wonder why they’re laughing or why that made them feel so uncomfortable, rather than tell them like why they’re a bad person or good person for feeling that way.” 10 And in numerous scenes, the show thumbs its nose at political correctness to create awkward moments with hopes of forcing America to grapple with issues of race, class, and sexuality through the trope of black popular culture.

With diverse characters and with diverse ranges, Glover’s Atlanta ultimately presents the underside of a “Tale of Two Cities” – Atlanta as an international Black Mecca, but one which fails most of black Atlanta. Atlanta abandons the “Black Mecca” and “Hotlanta” tropes by examining the lived experiences of Atlantans, who are black at all times; void of the western gaze or any interaction with whites. Sure, the main character Earnest “Earn” Marks (Donald Glover) is a Princeton dropout who is “dreamy and weird.” 11 However, unlike the other characters of Atlanta, with exception of his on-again-off-again girlfriend and daughter’s mother, Van (Zazie Beetz), Earn has awkwardly survived a weird white world outside of the grit and grind of Atlanta’s black masses, whose existence functions on the fringes of not only a white world of “Hotlanta,” but the “Black Mecca” trope as well. “All-Black Everythang Atlanta” is Earn’s natural habitat. He manages the rap career of his cousin, Alfred “Paper Boi” Miles (Brian Tyree Henry), a rising rapper grappling with the age-old dialectic of art’s imitation of life or vice-versa. Paper Boi is endearing and entertaining, but a close read of his character development shows him still reeling from the recent loss of his mother, which makes him simultaneously humble and “turnt up.” Paper Boi’s right-hand man and visionary Darius, an eclectic Nigerian American joins Earn and Paper Boi in their misadventures. Darius is witty and slick – dropping eccentric wisdom at the most awkward moments – and his presence lends credence to the immigration of international blacks to Atlanta. The allure of Atlanta to Africans, Afro-Caribbean and Afro-Europeans, a generation ago, strengthens the dynamism of a city with an already spirited black American majority.

Importantly, Glover’s Atlanta is only the latest iteration of Atlanta’s black expressive culture that challenges the “Black Mecca” and “Hotlanta” tropes. The series works in similar fashion to Atlanta’s emerging hip-hop scene of the 1990s when Atlanta-based OutKast and Goodie Mob had similar impact on national audiences with their albums of Southernplaylisticcadillackmuzik (1994) and Soul Food (1995) respectively. As national markets consumed these albums, they spoke to lingering tensions and trends that were particular to black Atlanta’s working and poor classes by detailing the franchising of the city for world consumption due to the Olympics, and how that process simultaneously disfranchised, criminalized, and demonized Atlanta’s black and poor indigenous citizens. Thus, Atlanta builds on a longer tradition of black Atlanta’s expressive culture, one that opens the city to social commentary from a new generation of artists who live in the city’s underbelly trampled over by Atlanta’s pursuit of a global commercial center. 12

Donald Glover’s Atlanta is unapologetic and unabashed black art created for blacks that dwell throughout the blackest parts of Atlanta. In this, Atlanta’s popular history is offset by Glover’s candid depiction of the city, exposing the smoke and mirrors of the “Black Mecca” and Hotlanta tropes. It rejects the representation of the city predicated on neoliberalism and demonstrates the further marginalization of the black masses through chic trends such as gentrification. Its awkwardness makes audiences uncomfortable by transposing Atlanta’s black masses to the center, and moving whites and the black upper and middle classes on to the fringes, places where they have little control over the narratives produced. And it builds on a longer-standing tradition of Atlanta’s black expressive culture that speaks to the issues experienced by Atlanta’s black masses. The anecdotes and aesthetics of the show are brilliant. This shows greatest contribution lies in the way it targets the experiences of Atlanta’s black indigenous citizens, offering a beautifully crafted demonstration of the pageantry of black Atlantan vernacular culture, peculiar to some and spot on to many.

Citation: Hobson, Maurice J.. “All Black Everythang: Aesthetics, Anecdotes, and FX’s Atlanta.” Atlanta Studies. November 15, 2016. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20161115.

Maurice J. Hobson is an assistant professor of African-American Studies at Georgia State University. He is the author of the forthcoming book The Legend of the Black Mecca: Myth, Maxim and the Making of Modern Atlanta and serves as a voice on black southern folk culture of the Black New South.

Notes

- W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches (Chicago: A. C. McClurg, 1903).[↩]

- Double consciousness as detailed by Du Bois speaks to black struggle with the multi-faceted conception of self. Here, he points out that blacks constantly work to reconcile two warring cultures to compose one identity … one black and the other American; who as he puts it “one ever feels his two-ness – An American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two reconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.” Ibid.[↩]

- The talented tenth is the idea to that promoted a leadership class amongst blacks based on liberal arts and professional education that would train a broadly defined black intelligentsia. In this, liberal arts education was necessary for building an autonomous black community because it disciplined and furnished the mind, developed character, and enriched life by encouraging future learning. The concept of the Talented Tenth is a byproduct of racial uplift theory of self-help and service to the black masses espoused by the black middle class, from which black elites and middle classes distinguished themselves from the black majority as agents of civilization. A central assumption of racial uplift ideology was that African Americans’ material and moral progress would diminish white racism. However, in its emphasis on class distinctions and patriarchal authority, racial uplift ideology was tied to the same pejorative notions of racial pathology bestowed upon blacks by whites. Ibid.[↩]

- “Atlanta, ‘Black Mecca of the South,'” Ebony, August 1971.[↩]

- Maurice Hobson, The Legend of the Black Mecca: Myth, Maxim and the Making of Modern Atlanta (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017); The Big Hustle was a moniker ascribed to Atlanta that indicated that the city was everything to everyone that had the resources to buy and create; The Sorrow City was ascribed to Atlanta by the STOP Committee, comprised of the missing and murdered mothers of the Atlanta Youth Murders’ victims.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- “With Atlanta, Donald Glover Wanted to Make “Twin Peaks for Rappers,” E! Online, September 6, 2016, http://www.eonline.com/news/792634/with-atlanta-donald-glover-wanted-to-make-twin-peaks-for-rappers.[↩]

- Ibid. Twin Peaks was an American television serial drama set in the fictional town of Twin Peaks, Washington. It explored the gulf between the veneer of small town respectability and the seedier life beneath. As the series progressed, characters that appeared to be innocent were revealed as dark characters leading double lives. Its tone was unsettling, which was consistent with horror films, but its melodramatic portrayal of quirky characters engaged in dubious activities and parodies. This show symbolizes an earnest moral inquiry distinguished by offbeat humor and surrealism.[↩]

- NPR Staff, Interview conducted and heard on All Things Considered, Atlanta, Georgia, 17 September 2016.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]