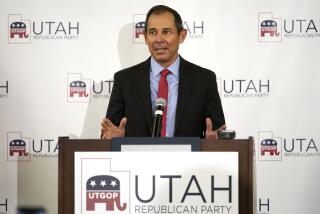

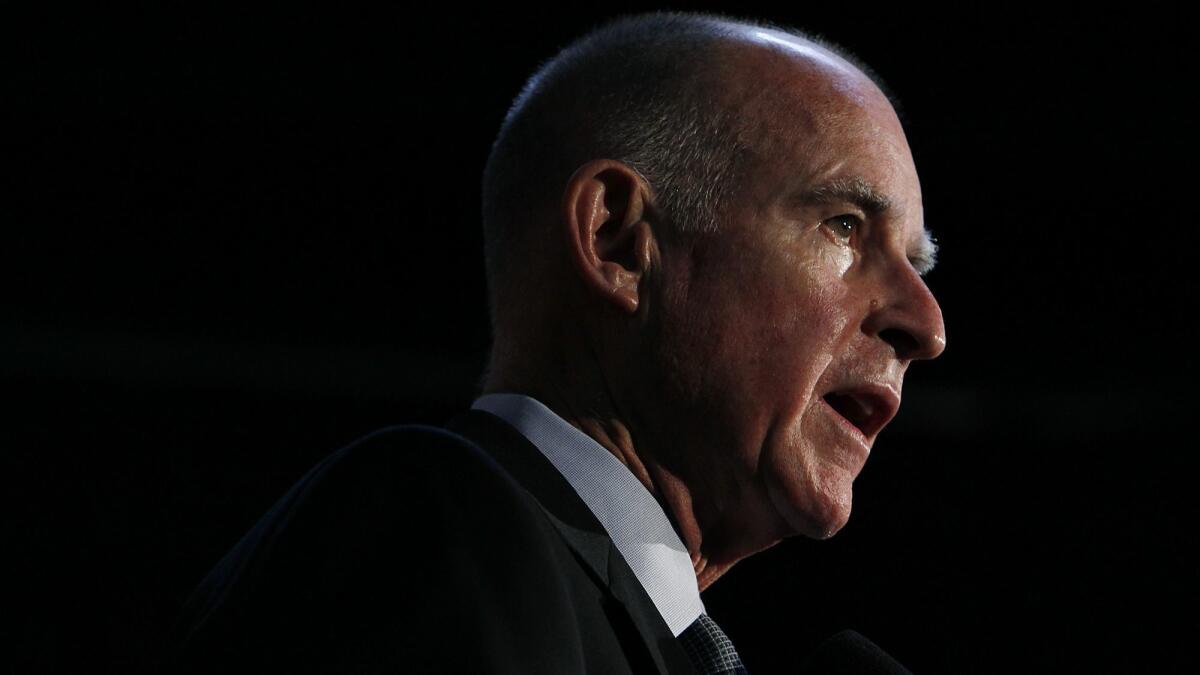

Op-Ed: Did Jerry Brown do enough on climate change?

Jerry Brown, in the last term of his two-part, 16-year governorship, came close to redeeming his environmental faults.

Brown deserves a salute for striving to get out the message that climate change is indeed, in his words, a global “existential crisis” and that we are living in the “new abnormal.” He has been doing what a U.S. president ought to do, finding allies among nations, regions and cities for a crucial struggle — in contrast to President Trump , who abdicated the job. Brown has delivered on what voters want from elected representatives: to determine what most threatens us and mobilize us to face the danger. He made California a world leader in climate change advocacy. He spent political capital and braved virulent criticism. He led.

“Jerry Brown’s biggest achievement as an environmentalist was to use the state of California to help foster more international cooperation on climate change,” Adrienne Alvord, western states director for the Union of Concerned Scientists, told me. “He single-handedly managed to keep some momentum for international cooperation going in the United States.”

Brown’s climate efforts have been profoundly important; it’s a measure of the breadth of the environmental crisis that they haven’t been nearly enough.

Brown enlisted China’s support in the climate struggle, and the ensuing Sacramento-Beijing connection led to China’s indispensable backing of the 2015 Paris climate agreement. Brown and the governor of Germany’s third-largest state devised the “Under 2” memorandum, which commits signers to accelerate actions to keep global temperatures from rising more than 2 degrees Celsius. The memorandum is now supported by 220 governments, representing 43% of the global economy.

In California, Brown put his policies where his mouth was. In his 2015 inaugural address, he laid down ambitious 2030 targets for reducing vehicle petroleum use, increasing use of renewably derived electricity, reducing emissions of methane and other highly potent climate pollutants, doubling the heating efficiency of existing buildings, and making heating fuels cleaner — at a time when public discussion of such issues as building codes and heating fuels was scant. California is addressing most of these fronts, culminating in September in Brown’s signature on legislation requiring all retail electricity to be 100% carbon-free by 2045.

Yet for all that, Brown’s advocacy was too limited. He worked only the demand side of the climate equation; he campaigned on reducing fossil-fuel emissions but did nothing to cut the supply of oil generated in the state. Considering that California is the nation’s third-largest oil producer — of heavily climate-negative crude — and the nation’s third-largest oil refiner, that’s a substantial omission. In 2011, Brown even fired two state officials who applied rigorous standards to oil drilling applications, and he boasted six months later that permits had gone up by 18%.

Supporters of Brown’s approach say that if California cuts its oil production, producers elsewhere will take up the slack, depriving the state of jobs. But unless the state curbs its oil supply, it will overshoot its climate emissions targets by about 40% through 2050, according to the Huntington Beach-based Communities for a Better Environment.

Back in Brown’s freewheeling first run as governor, from 1975 to 1983, he gave wide latitude to his environmental appointees. Huey Johnson, a combative environmentalist who served as resources secretary from 1978 to 1982, told me recently that Brown never questioned even his controversial decisions. One laudable result was the hard-won 1981 designation by the federal government of 1,200 miles of California rivers as wild or scenic, protecting them from development.

In his second governorship, Brown has picked his fights more carefully. He at first focused on strengthening the state’s battered economy, then shifted his attention to the climate struggle. As the state tacked toward clean energy, its prosperity dismantled the Republican argument that climate-positive policies were economy killers.

But Brown wasted opportunities with his fixation on the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta twin tunnels — an expensive, clunky solution to the state’s water supply vulnerability. By holding out for the twin tunnels, he lost the chance to embrace a smaller, single-tunnel design that might have gained more support among environmentalists. Now the entire modernizing project may founder.

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute from L.A. Times Opinion »

He should have spent more time championing cheap local solutions to the state’s water problems, such as stormwater capture, aquifer storage and water recycling. His most notable achievement in the water realm was passage in 2014 of the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, a cautious step toward needed regulation that moves the state’s groundwater policies from the 19th century into the 21st.

In environmental justice, Brown’s record was undistinguished. He failed to put political muscle behind efforts to provide clean drinking water for a million Californians who now lack it. And he showed little interest in protecting people from toxic air and water pollutants generated by nearby oil-drilling, fracking and refining installations. He has used wildfire effectively to proselytize for climate action, but his solution — more money for forest logging — isn’t what most California fire and forest ecology experts stress.

In recent years, the state has suffered an array of environmental woes, to varying degrees climate-related: the catastrophic fires, drought, heat waves, encroaching sea levels, dwindling fish stocks, toxic air quality, to name just a few. Brown’s climate efforts have been profoundly important; it’s a measure of the breadth of the environmental crisis that they haven’t been nearly enough.

Jacques Leslie is a contributing writer to Opinion.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinionand Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.