Walter Isaacson on the traits of "Innovators"

Many of the most important dreamers and doers of our high-tech age are finally getting the recognition they deserve, thanks to a writer who makes spotting genius his business. Rita Braver has been watching him at work:

It's the San Francisco Techcrunch "Disrupt" conference, showcasing the latest digital products

And just when you're thinking, "Everyone looks so young," you catch up with a silver-haired fellow who knows just what to watch for:

"Instead of looking at a product, I tend to look at the people behind it and say, 'Are they gonna be able to innovate, and change when their original plan doesn't work?'" said Walter Isaacson.

Isaacson has spent years studying what it takes to make in the Internet era. His biography of Steve Jobs was the top-selling book of 2011.

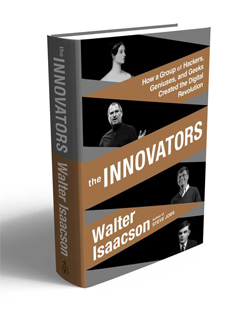

This month, he's out with "The Innovators," published by CBS's Simon and Schuster. Already nominated for a National Book Award, it's the story of how a group of visionaries -- many of them unsung -- created the computer and Internet revolution.

What made them succeed? What traits did it take? "I wanted to give real, concrete storytelling meaning to, 'What does it mean to be an innovator?'" said Isaacson.

Case in point: Ev Williams, a college dropout, who's a creator of both Blogger.com (the first program making it easy to blog) and Twitter.

Today, with his net worth estimated at $3 billion, he says he wasn't sure that either project would take off.

"You can look back and say, 'Yes, I knew exactly that the world needed this," said Williams. "But it's really a process of discovery, I think. It's like you're exploring, and you're going by your gut."

Isaacson says the genius of people like Williams is that they see things in ways that the rest of us can't: "They take all the little things that are there, the building blocks that have already been created, and they do something creative and imaginative," he said.

You might be surprised to learn one of the pioneers Isaacson credits with first imagining what a computer might do was a woman, born in the early 19th century.

Ada, Countess of Lovelace, lived from 1815 to 1852, dying at the age of 36. The daughter of the Romantic poet, Lord Byron, she was a mathematician who was intrigued by the use of punch cards, which had recently been introduced to program automatic looms. She prophesied that similar devices could also be used for complex math problems, and much more.

"They could even compose music, they can make art, they could, of course, do calculations with numbers," said Isaacson. "And so by envisioning how those cards could be used on a computer, she says, 'A computer can be general purpose; it doesn't just have to be for numbers.'"

But it wasn't until almost a century later, in the U.S.A. during World War II, that the first modern multi-purpose computers were built for defense purposes.

As to who deserves credit for inventing the computer? Isaacson calls it "a wonderful historical wrestling match."

The contenders are on view at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, Calif. There's a replica of a computer designed by John Vincent Atanasoff at Iowa State University in the early 1940s. It barely worked.

But in later years, Atanasoff, the Iowa inventor, would claim the Penn team copied some of HIS technology.

Braver said, "So there were lawsuits forever. Did anybody end up with a patent, and the title of who invented the first computer?"

No, said Isaacson. "First of all, we don't want to let just the courts make that decision. We historians get to make it. But secondly, the courts couldn't make that decision. Nobody really got a patent saying, 'You own the rights to the computer.'"

Isaacson says it was big news on Election Night in 1952 when CBS News introduced a Univac Computer. It correctly predicted the presidential election, though Walter Cronkite didn't trust it enough to go with the results.

"Cronkite's a little bit worried and sort of doesn't say anything for a while, and says, 'Well, we don't have a projection yet,'" said Isaacson. "But it just shows that a computer can be used for really practical things."

And did you ever wonder WHY we say our computer has a bug in it?

"Grace Hopper and her team did the programming for Mark I at Harvard, one of the big, early computers," said Isaacson. "And one night it wasn't working very well. And they opened it up, and there was a moth in one of the switches. And so that's why we call it debugging."

You might not expect Walter Isaacson to be a tech junkie, considering that he and his wife, Cathy, live in the decidedly un-techie Georgetown section of Washington, D.C. A former managing editor of Time magazine, since 2003 Isaacson has been the CEO of the Aspen Institute, a policy study organization.

He's also earned a reputation as an expert on genius, after writing bestsellers on the likes of Steve Jobs, Albert Einstein and Benjamin Franklin.

"It seems like the people in your current book are such a long distance from someone like Benjamin Franklin," said Braver. "Are there parallels?"

"Oh, absolutely," replied Isaacson. "I think if Benjamin Franklin came back today, he'd sort of fire up a website, and he would love to sort of look at my iPhone and figure how to make an app himself, because he was always inventive. Those traits of his, I see in the innovators I write about today."

But though his past books have focused on individual achievement, Isaacson has come to realize that most history isn't made that way:

"So it isn't really that one guy who makes the whole difference?" asked Braver.

"You know, the dirty little secret is, that those of us who write biographies know that we distort history a little bit," Isaacson said. "We try to make it seem like one guy sitting there in the garage created everything, and I really wanted to remedy that with this book. To say, it's not just a lone inventor, it's the collaboration and team work that makes for innovation."

It's also building on the work of others. ALTAIR, the very first and very primitive personal computer, was made by a hobbyist named Ed Roberts in Albuquerque. It had no monitor or keyboard, yet it appeared on the cover of Popular Electronics.

"And the world is never the same," said Isaacson. "All sorts of young people say, 'I wanna be involved.'"

And it would take young teams -- like Paul Allen and Bill Gates (who started Microsoft), and Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs (who founded Apple) -- to actually make the personal computer a really useful tool.

In fact, Walter Isaacson says that in the end, the digital revolution is really a cavalcade of both dreamers and doers.

"You know, vision without execution is just hallucination," he said. "You've got to have teams of people who have great visionaries, but also people who get things done. It's when you combine the imagination of humans with the processing power of machines -- that's where the real innovation comes."

WEB EXCLUSIVE: Book excerpt from "The Innovators"

Read the introduction to Walter Isaacson's story of the "hackers, geniuses and geeks" who created the digital revolution.

For more info:

- "The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution" by Walter Isaacson (Simon & Schuster); Also available in eBook, Unabridged Audio Download and CD, and Abridged Audio Download and CD formats

- Follow @WalterIsaacson on Twitter

- The Aspen Institute

- Disrupt SF 2014 Conference