This advertising content was produced in collaboration with our partner, Virginia Wine.

In Virginia, over 400 years of viticultural history are the backdrop for a modern industry that kickstarted a half-century ago, making it one of the most exciting wine states in the U.S. This energetic industry has exploded from just six pioneers in the 1970s to 312 wineries across ten regions and eight AVAs today.

Thus far, much of Virginia’s wine culture has unfolded thanks to secondary Old World varieties that have thrived when given the chance to take center stage. Grapes like Cabernet Franc and Viognier—which historically took a backseat in their native regions—have quickly become Virginia staples, while offbeat players like Petit Manseng and Petit Verdot are surprising professionals with phenomenal quality. At the same time, familiar varieties like Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Merlot showcase Virginia’s ability to straddle both Old World and New, marrying elegance and minerality with round body and bold fruit.

Virginia’s small growers and producers have long realized that their land had a sense of place to express through its wines, and they are now urging others to pay attention to the specificities of this diverse terroir as well. From rocky mountain slopes to sandy waterfront shores, Virginia is brimming with character—and the state’s vintners are harnessing their experimental spirit to uncover it.

Don’t miss the latest drinks industry news and insights. Sign up for our award-winning newsletters and get insider intel, resources, and trends delivered to your inbox every week.

Geography

While Virginia’s relatively new status as a major wine-producing state leads many people to view the state as a wine region of a singular landscape, in reality, Virginia’s geology is exceptionally diverse. The state is home to five major geologic regions that range from zero to 5,729 feet in elevation, with soil parent material that ranges from sedimentary to metamorphic rock.

West of the Blue Ridge Mountains, sandstone and limestone are most prevalent in Virginia’s inland regions. Metamorphic rock and ancient volcanic soils dominate in the central Blue Ridge and Piedmont regions, with more sandstone and shale in the former compared to the latter’s concentration of gneiss, schist, and greenstone. Young clay and sand take over as elevations slope towards the sea in Virginia’s coastal plain.

With latitudes ranging from 36 to 39 degrees, climatic conditions vary from inland plateaus, through the Blue Ridge Mountains, to maritime shores. Overall, Virginia tends to be warm and hospitable, with fewer harsh swings from cold winter snaps to blazing summer heat waves, allowing the state to grow a wide range of grapes. Rainfall and humidity are characteristic elements of Virginia’s climate, with four distinct precipitation areas ranging from 39 to 45 inches of rainfall per year. Unlike many major international wine regions, rain is typically distributed evenly throughout the year.

History

A budding winegrowing region with a long history of viticulture, Virginia has an opportunity to harness the energy of youth while drawing on centuries of tradition. The state’s first vines were planted shortly after English colonists settled in Jamestown in the early 1600s, and locals made many attempts to cultivate vines—both vinifera and local varieties—in the years to come.

One of Virginia’s historical contributions to American wine is Norton, a native American grape first cultivated in Virginia in the 1820s. Not only did Norton prove to produce award-winning wines throughout the 19th century, winning “best red wine of all nations” at the 1873 Vienna World’s Fair, it is also credited with helping European wineries overcome phylloxera.

Virginia winemakers also successfully experimented with the technique of grafting vinifera grapes on American rootstocks around this time. However, Prohibition halted the industry’s momentum, and Virginia’s devotion to viticulture was largely forgotten throughout much of the 20th century.

In the 1970s, however, Virginia’s wine industry was reborn when a group of six winemakers found new success growing vinifera grapes. By 1995, the state had 46 wineries, and by 2005, there were 107. Today, Virginia counts more than 300 wineries among its ranks, making the state one of the fastest-growing wine industries in the U.S.

Appellations

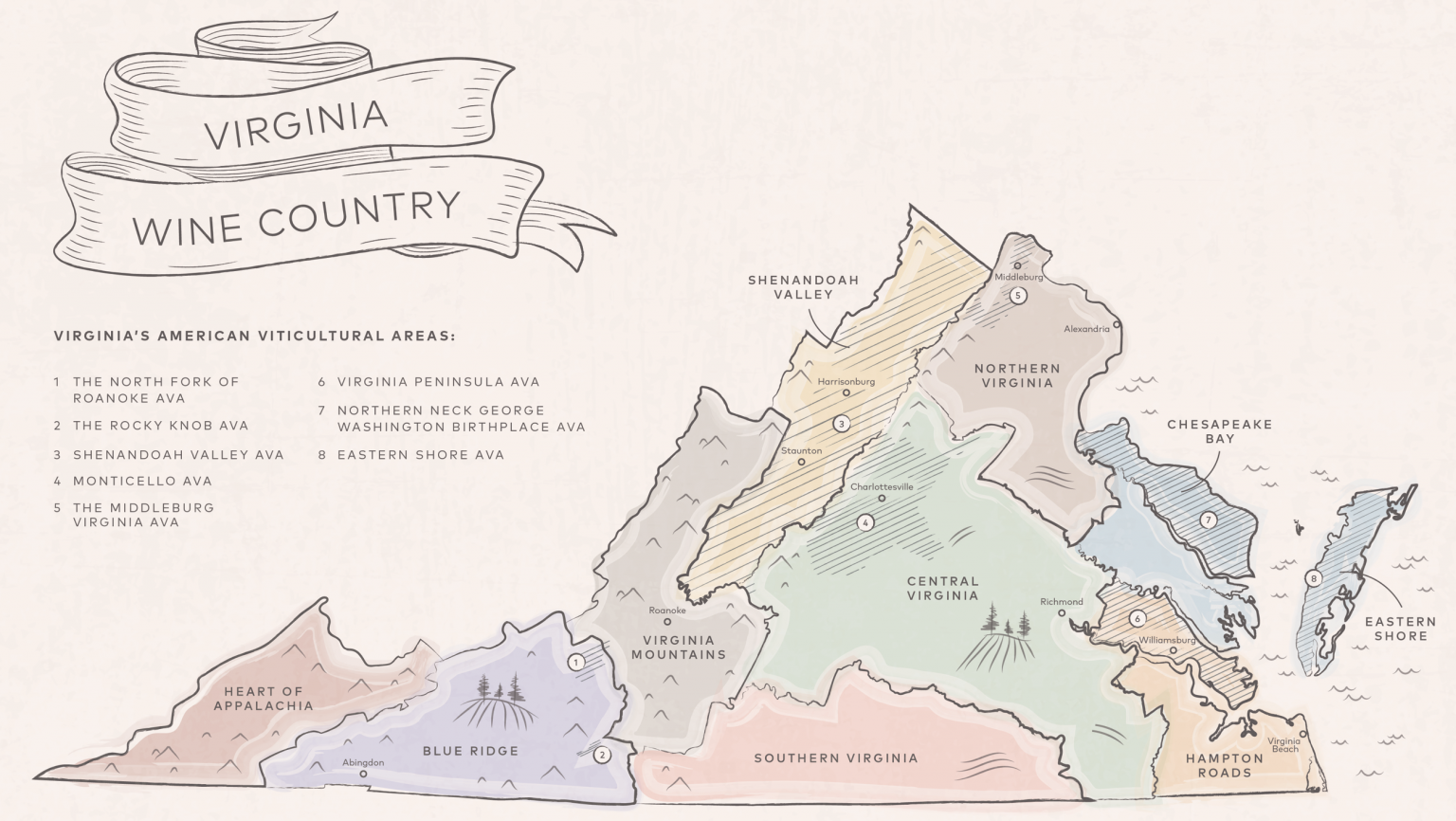

Virginia is home to eight AVAs located within 10 regions: Blue Ridge, Central Virginia, Chesapeake Bay, Eastern Shore, Hampton Roads, Heart of Appalachia, Northern Virginia, Shenandoah Valley, Southern Virginia, and Virginia Mountains. The state’s 4,000 acres of vines are primarily located in Northern Virginia and Central Virginia regions, but quality wine is made throughout. In order for a wine from Virginia to have an AVA on the label, 85 percent of the grapes must come from that AVA.

The Middleburg Virginia AVA

This Northern Virginia region, located just 50 miles west of Washington, D.C., was only established in 2012, but it is one of the state’s fastest-growing AVAs. It is home to 229 acres of commercial vineyards and 24 wineries, situated amidst winding back roads across rolling hills. The Potomac River bounds the AVA to the north, and it’s surrounded by mountains to the east, south, and west. Granite and sandstone soils provide good drainage for Bordeaux varieties, Viognier, and Chardonnay, and both single varietal wines and blends are crafted here.

Shenandoah Valley AVA

The state’s largest AVA, Shenandoah Valley AVA spans several counties in Virginia and West Virginia, bounded by the Blue Ridge Mountains to the east and the Allegheny Mountains to the west. Protected from Atlantic wind and rain by the mountain ranges, these valley vineyards are drier than the rest of Virginia. Across the state, a variety of grapes are grown (including hybrids), but many of the state’s major vinifera grapes are grown in Shenandoah’s rocky, fertile soils.

Monticello AVA

This historic area is home to Virginia’s oldest AVA, created in 1984. It’s located in the central Piedmont area, near the bustling city of Charlottesville, and is home to many wineries, making it a popular wine tourism center. The land here is hilly, with many vineyards planted along the eastern slopes of the Blue Ridge Mountains in fertile, granite-based clay. Winemakers work with some of the state’s most popular varieties, including Viognier, Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Cabernet Franc.

The North Fork of Roanoke AVA

Located within the Blue Ridge region in southwestern Virginia, the North Fork of Roanoke’s vineyards run along the Roanoke River, situated on the eastern slopes of the Allegheny Mountains. It’s known for Bordeaux blends and varietal wines made from Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, and Merlot, but winemakers here experiment with a number of other grape varieties as well.

The Rocky Knob AVA

South of the North Fork of Roanoke AVA is Rocky Knob, where vineyards are located on the eastern slopes of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Well-drained loam and gravel soils create well-structured and intensely-flavored wines.

Northern Neck George Washington Birthplace AVA

Along the western shores of the Chesapeake Bay, vineyards benefit from the moderating effect of the nearby waterfront. Planted in sandy loam soils are some of Virginia’s most prolific grapes, like Chardonnay and Cabernet Franc, along with hybrids like Vidal Blanc and Chambourcin.

Eastern Shore AVA

On the southern end of the Delmarva Peninsula is the scenic Eastern Shore AVA, which is bordered by both the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. A distinctly maritime climate with strong summer breezes extends the growing season, creating bright, characterful Chardonnay and Cabernet Franc wines.

Virginia Peninsula AVA

Virginia’s newest AVA incorporates a cradle of American history—Williamsburg—and while not exactly settled for its viticultural potential, it currently has two wineries. Bound by the broad James and York River estuaries, the narrow AVA runs about 50 miles in length, toward Richmond, and varies from 5 to 15 miles in width. A maritime influence moderates the average low and high temperatures. The soil is sedimentary in nature.

Key Grape Varieties

More than 28 grape varieties are grown in Virginia’s vineyards. Viticulture is evenly split between red and white grapes, which are used to make wines of all colors and styles: from dry to sweet, still to sparkling, and encompassing white, red, and rosé wines. Vinifera vines dominate, but winemakers also work with hybrid varieties and American grapes like Virginia’s native Norton.

The list of grape varieties cultivated in Virginia is filled with familiar characters like Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Merlot, but these wines are far from ordinary. Virginia’s unique juxtaposition halfway between Europe and California adds local character to these well-known varieties, blending Old World and New World to upend notions of what these varietal wines typically taste like.

But many of Virginia’s most popular wines stem from grapes that might have traditionally been overlooked in the Old World. Viognier and Cabernet Franc may not have taken center stage in their home regions, but they thrive in Virginia’s vineyards. Driven by innovation, winemakers are experimenting with new grape varieties every year, with Virginia wines made from Petit Manseng, Nebbiolo, Petit Verdot, Vermentino, and more all garnering acclaim from consumers and professionals alike.

While varietal wines are common, Virginia first gained recognition for its red blends from Bordeaux varieties, which are still foundational wine styles for local vintners. Blending allows winemakers to work with fruit from the state’s variable mesoclimates and manage unpredictable vintages. High-quality rosé and sparkling wines are also gaining steam in Virginia and attracting outside attention to the state’s wines.

Cabernet Franc

First planted in 1977, Cabernet Franc has quickly become a standout variety in Virginia, now comprising 12 percent of the state’s vineyards. It’s rainfall-resilient, and Virginia’s warmth helps to manage the grape’s natural pyrazines. Winemakers are increasingly focused on coaxing out the nuances of fruit planted in differing soils, since this terroir-expressive variety can thrive in well-drained, rocky soils as well as heavy, water-laden soils. Cabernet Franc is often oaked, and it is used in both varietal and blended wines.

Chardonnay

As the most-planted white grape in Virginia (13 percent of vineyards), local Chardonnay styles range widely. High-elevation styles can be quite Burgundian in nature, while those planted at lower elevations are often richer and more robust. Depending on the winemaker’s preferred style, Virginian Chardonnay may be bright, lean, and unoaked, full-bodied and complex, or even sparkling.

Cabernet Sauvignon

Accounting for five percent of Virginia’s plantings, Cabernet Sauvignon works best when planted in areas with well-drained gravel or shale soils. It often bridges the gap between Old World and New, with more elegance and restraint than typical California iterations, and it is often found in the state’s popular Bordeaux-style blends.

Merlot

Grown in sandy loam and clay soils and comprising eight and a half percent of vineyards, Merlot from Virginia adds elegance to red blends. As a varietal wine, it is made in a range of styles, from approachable to complex.

Petit Verdot

Comprising seven percent of Virginia’s vineyards, Petit Verdot has become an important variety because it ripens earlier and more easily here than it does in Bordeaux. Used in both varietal wines and blends, it’s typically rich and deeply colored, with structured tannins.

Viognier

A breakout grape for the state, Viognier was first planted in 1990. It makes up six percent of Virginia’s vines and succeeds in granitic and alluvial soils. The aromatic grape has been embraced by Virginia winemakers, who make it in many styles: dry or sweet, oaked or unoaked.

Other Notable Varieties

Some of Virginia’s most exciting wines are being made from varieties that are obscure or rarely grown in the U.S.; other varieties comprise nearly half of Virginia’s vineyard plantings. Petit Manseng is a new standout, as its loose grape clusters work well in the state’s humid climate. The wines may be dry or sweet and always have bright acidity.

Other experimental vinifera varieties include Tannat, Vermentino, Nebbiolo, Albariño, and Rkatsiteli, while some winemakers are starting to work with grapes like Pinot Noir and Sauvignon Blanc. There has also been a movement to reclaim American grapes like Norton to make fresh and fruity wines.

What’s Happening in Virginia Today?

Every vintage in Virginia is a new adventure, but while some vintners might see this as a challenge, Virginia’s winemakers embrace it as an opportunity. Though vintages can be unpredictable, they also require vintners to tune into every aspect of their land. While modern winemakers understand that centuries of history have come before them, they also know that they are writing part of Virginia’s wine history now—and they believe that the best years are still ahead.

Currently, there are over 4,000 acres of vines planted in the state of Virginia, and that number continues to increase, allowing producers to bolster the state’s most successful grapes while also experimenting with new ones. At the same time, the average size of a Virginia winery is just 12.8 acres, and most are family-owned. These artisanal winemakers are working together to learn, grow, and innovate, taking a long-term approach to shape a promising future for their local industry.