More than two months ago, House Democrats started the process of passing a bill that would gradually raise the federal minimum wage to $15 per hour.

Since then? Crickets.

Here’s a look at the complex factors involved in making such a move.

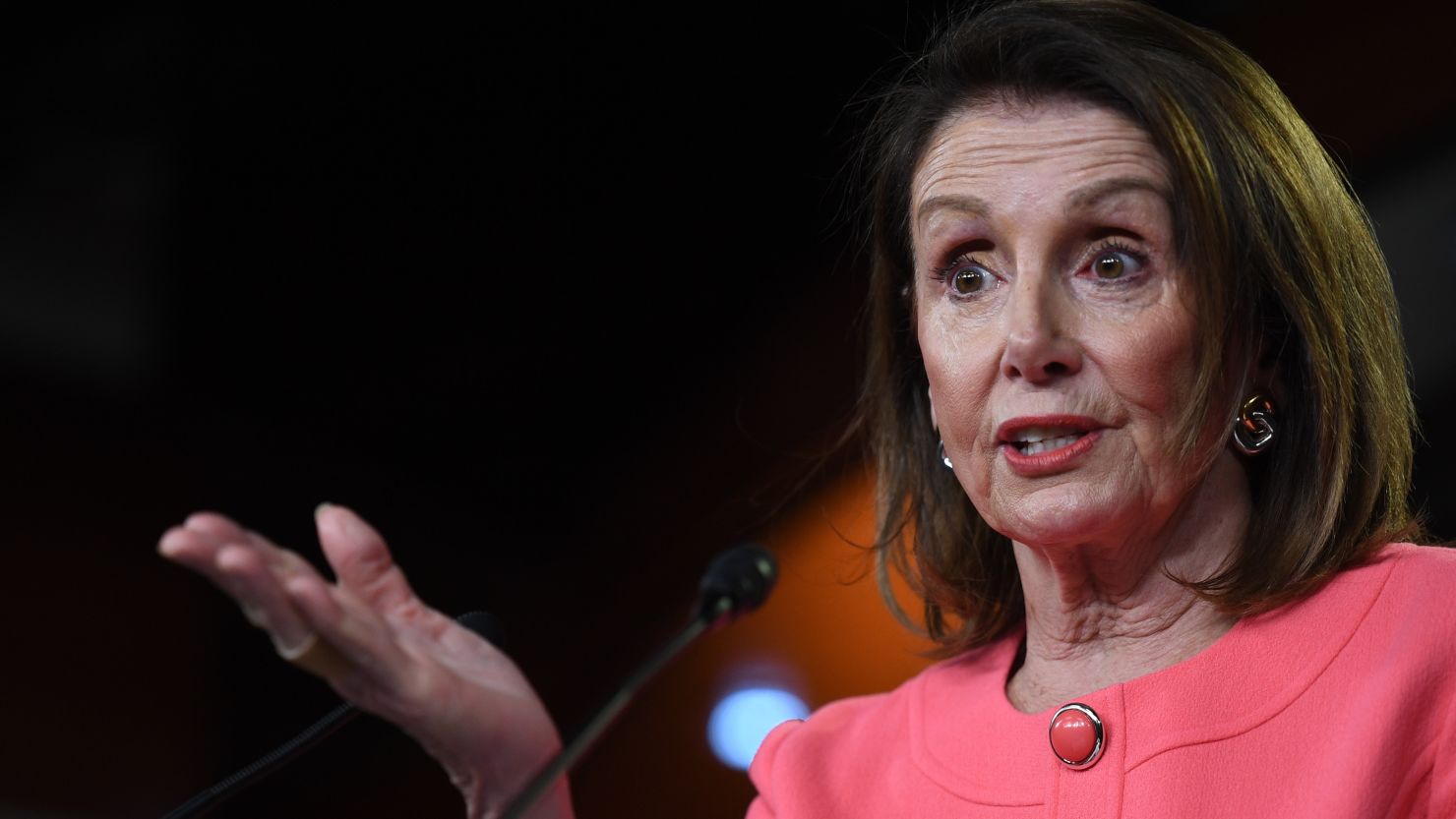

Pelosi promised action in first 100 hours

It’s a far cry from Nancy Pelosi’s 2017 pledge that if Democrats took control of the House “in the first 100 hours we will pass a $15 minimum wage.”

Months later, House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer told reporters Democrats will move to the bill. But they need more time.

“We’ll get the votes for the minimum wage bill, but there are discussions about how we can, what actions, if any, should we take to make sure that it is fair,” he said Thursday on Capitol Hill.

In addition to there being red states and blue states, it turns out there are high-cost states and low-cost states. And a single minimum wage might not be the thing to bind them.

Despite the rhetoric and promises in 2018 and the importance of economic inequality as a Democratic issue on the 2020 campaign trail, the Democratic Party is split.

Nearly everyone in the party wants to raise the minimum wage. But Democrats who hail from states and districts where it’s not as expensive to live are not as keen on that $15 figure. At least not right now.

It’s not clear at this point when or even if House Speaker Pelosi will move toward the $15 minimum wage bill. (And even if she does, the bill faces a very uncertain future in the Republican-controlled Senate). One alternative to a blanket $15 federal minimum wage, being pushed by moderate Democrats like Rep. Terri Sewell of Alabama, would calculate a minimum wage regionally.

The advantage, said Sewell in April, is that this proposal “provides all minimum wage workers with a much-needed raise while protecting jobs, giving every community the flexibility to grow their economy and taking into account that the cost of living in Selma, Alabama is very different than New York City.”

A decade of no wage hikes

It’s been 10 years since the federal minimum wage went up. The bill that passed through committee earlier this year would raise the minimum hourly wage from the current $7.25 to $15 over five years. Thereafter, it would enable automatic annual hikes based on increases in the median hourly wage as determined by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, an important feature of the $15 wage bill – the Raise the Wage Act – that would make another 10-year lull unlikely.

There was no federal minimum wage until 1938, and it’s been raised periodically. But Congress hasn’t approved a new wage hike since 2007, when President George W. Bush signed the current wage into law. The last hike approved through that law went into effect in 2009.

$7.25 doesn’t go as far as it used to

The dollar isn’t worth what it once was, of course. It would take about $8.60 in 2019 to equal the buying power of $7.25 in 2009, according to one government inflation calculator.

The $15 value has been repeated by Democrats in Congress and some presidential candidates like a mantra in recent years as they criticize corporations, saying they’re undervaluing their employees. It’s a key way they contrast themselves with Republicans, who have focused on helping corporations and businesses with a permanent tax cut rather than workers with a guaranteed higher wage.

But there is some recent research on local minimum wage hikes that challenges the long-held view that a higher minimum wage leads to fewer total low-wage jobs. In today’s economy, with an unemployment rate under 4%, fewer jobs might not be a problem anyway.

Even if Democrats can figure out how to pass a $15 minimum wage, that isn’t a number that will wipe out poverty or even lead to a living wage – enough to cover a worker’s expenses – everywhere in the country.

White House adviser calls a wage hike ‘silly’

While President Donald Trump was on both sides of this issue during his campaign in 2016 and said certain states need much higher wages, his White House has been cool to the idea of a minimum wage increase.

“My view is a federal minimum wage is a terrible idea. A terrible idea,” Trump’s top economic adviser Larry Kudlow told The Washington Post in November. He called the notion of a federal minimum wage hike “silly.”

Who makes minimum wage?

About 81.9 million workers over the age of 16 were paid by the hour in 2018. And 1.7 million of those hourly workers, 2.1%, were paid at or below the minimum wage, according to BLS. The percentage of men making at or are at below the minimum wage is less, 2%, while the percentage of women is a little higher, at 3%.

The data BLS uses is from a government survey and relies on what wage workers say they make, as opposed to what wage employers say they are paying.

Workers making minimum wage tend to be young, according to BLS, and include a slightly larger percentage of black workers than other racial subgroups. More part-time workers reported making the minimum wage or less than full-time workers. About 60% of the people who reported earning wages at or below the minimum worked in the leisure and hospitality industry, predominantly in restaurants, where their wages may be supplemented by tips.

Tipped workers can be paid less than the minimum wage, but the Raise the Wage Act would end that disparity.

Cities, states and voters have moved on their own

There is already a regional minimum wage of sorts. States and cities have been passing their own laws, to the point that more than half of the states – 29 – have higher minimum wages than the federal government, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

And more state hikes are on the way. Maryland lawmakers overrode the veto of the state’s Republican governor to raise the minimum wage there to $15 by 2025. Vermont has considered legislation that would raise its minimum wage to $15 by 2024 and Connecticut’s lawmakers are considering a bill that would do the same by 2023.

Other legislatures see things differently. In Arkansas, voters overwhelmingly passed an initiative last November to raise that state’s minimum wage to $11 by 2021 despite opposition from their governor. Some state lawmakers are looking to gut the measure, although the governor says it should stand.

Cost of living varies by region

This is an important regional aspect that helps explain the position of Democrats like Sewell; workers in the South are more likely to be paid hourly – 35% of workers there said they were, compared with less than 25% in every other region of the country. And among those paid hourly, half of them in the South – where there are almost no higher-than-federal minimum wage laws – made at or below the federal minimum wage. Less than a quarter of hourly workers in every other part of the country said they made at or less than the federal minimum wage. But again, there are many more higher-than-federal minimum wage laws in those states.

Even those laws aren’t enough, according to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s living wage calculator, which was created by professor Amy Glasmeier. Her data suggests that different areas have different needs and so do different families. So she took cost-of-living data for every city and county nationwide and calculated what an individual needs to live. She also includes what families of varying sizes need.

In Mississippi, where there is no state minimum wage, so the federal wage of $7.25 is in effect, she calculates a living wage at just more than $11 per hour for an individual.

$15 isn’t always enough

In Washington state, which includes super-expensive Seattle, the statewide living wage is $13.30. The state’s minimum wage will kick up to just more than that in January 2020, which is great for the state but wouldn’t be enough for low-wage earners in Seattle, where the living wage for an individual is calculated at $15.05. Seattle’s citywide minimum wage is just below that at $15 per hour, although some big companies must pay $16 as part of the city law.

San Francisco’s living wage is more than $18 for an individual and more than $36 for an individual with a child. The minimum wage there, which is tied to inflation and the Consumer Price Index, will rise to $15.59 in July. That’s a lot more than you might need to live in parts of Mississippi or Alabama, but maybe not enough in San Francisco.

Pressure has brought change to Amazon, McDonald’s

Some businesses also are moving on their own.

Amazon buckled to pressure from the likes of Sen. Bernie Sanders to raise its minimum wage from around $11 for new employees to $15.

“We listened to our critics, thought hard about what we wanted to do and decided we want to lead,” said Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s founder and CEO. “We’re excited about this change and encourage our competitors and other large employers to join us.”

McDonald’s told the National Restaurant Association in March that it would no longer be involved in any active lobbying against minimum wage hikes.

Target has set a 2020 deadline to raise its lowest wage to $15. It’s currently $12.

Companies are also having trouble filling jobs

“I think Target’s move is simply a reflection of the fact that we’re near full employment and it is extremely difficult to get employees to work,” former McDonald’s USA CEO Ed Rensi said on Fox Business in April.

“I had dinner with a bunch of McDonald’s franchisees the other night and they are struggling to find employees at any price,” he added. “I see some of them (offering) $16, $17 per hour, and they still can’t find employees.”

However, small business owners might see things differently from a large chain or even a franchise, Jon Kurrle, vice president of federal government relations at the National Federation of Independent Business, told CNN in April.

“A larger company can absorb costs in a way that a smaller business can’t, and also make technology investments in a way that not all small businesses can,” he said.